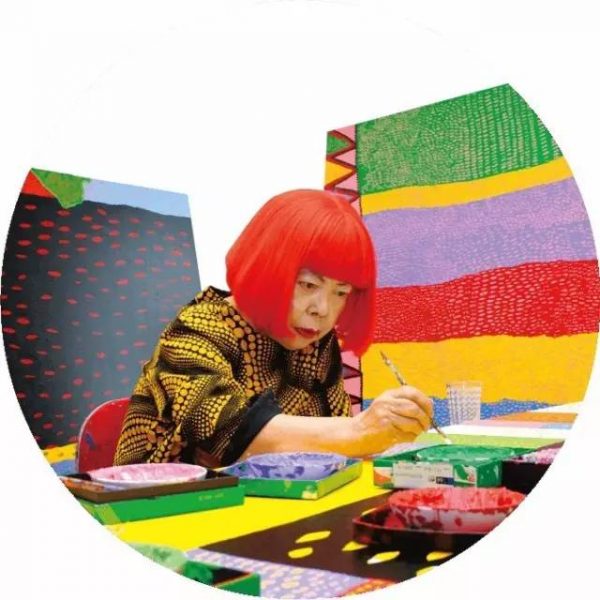

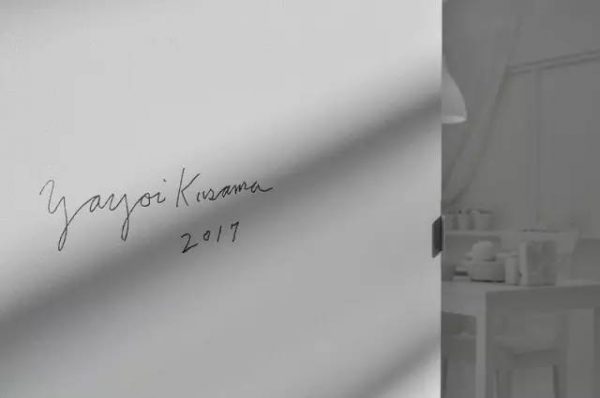

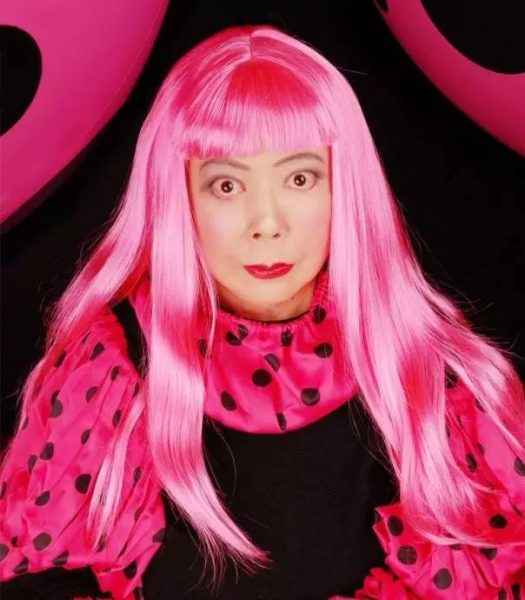

87 and as young as ever: Time magazine recently named Yayoi Kusama one of the world’s ‘100 Most Influential People’. Her recent ‘My Eternal Soul’ solo exhibition in Japan was set to be one of Kusama’s biggest ever shows in the capital and will consist mainly of large-scale paintings from the eponymous series the artist has been working on since 2009. Visitors will also be able to trace Kusama’s career from her early years in France and New York all the way up to the present.

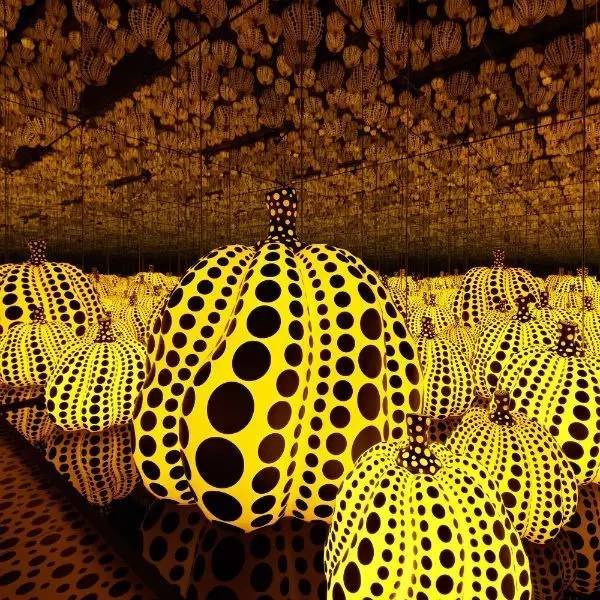

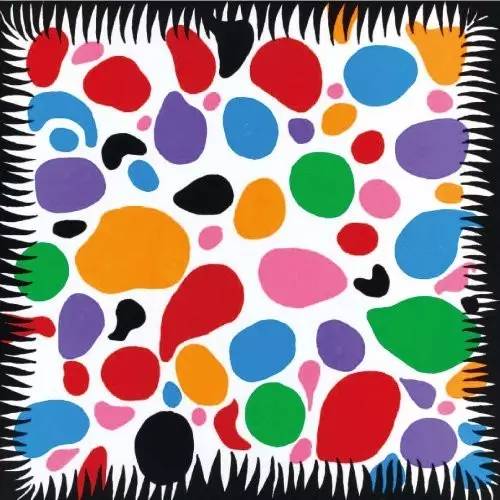

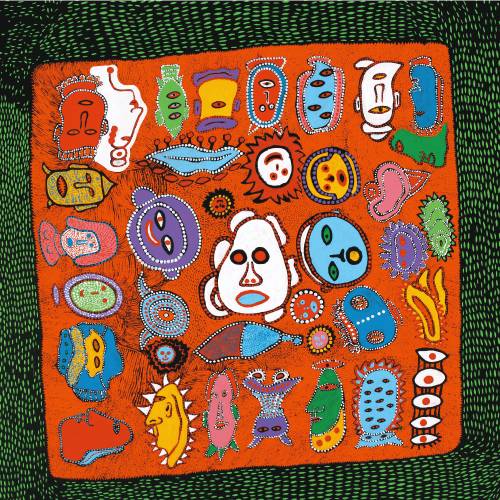

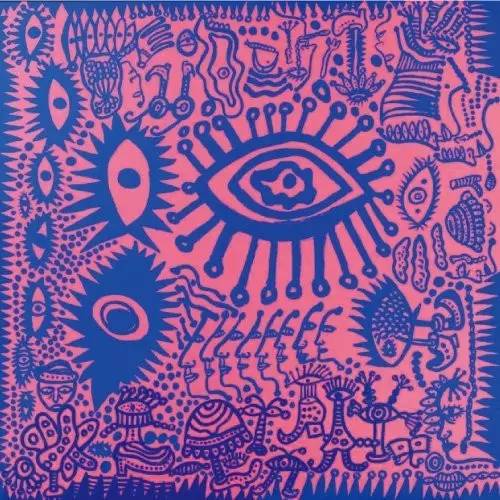

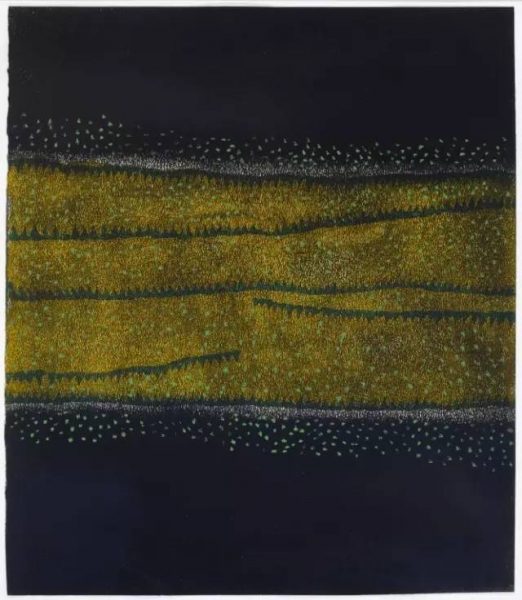

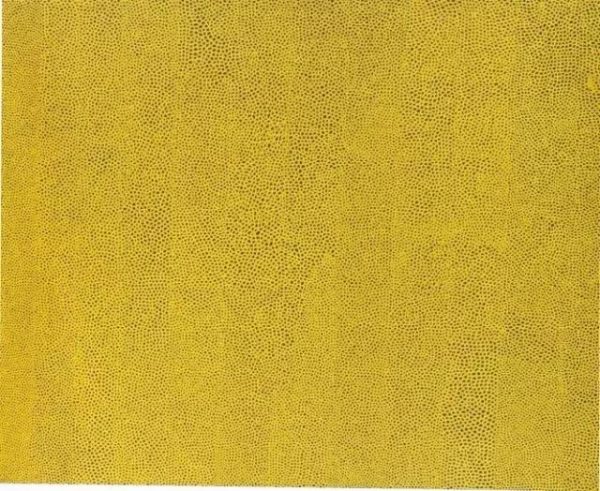

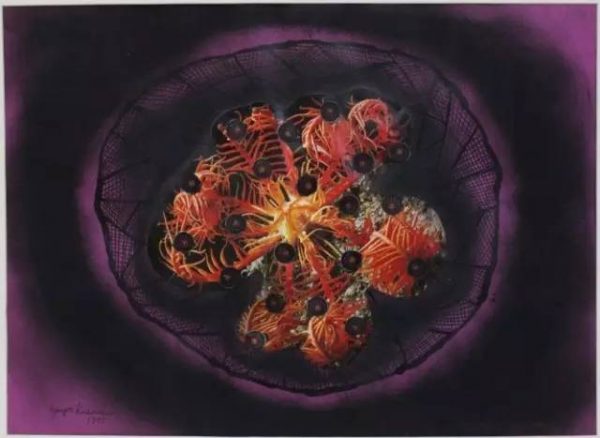

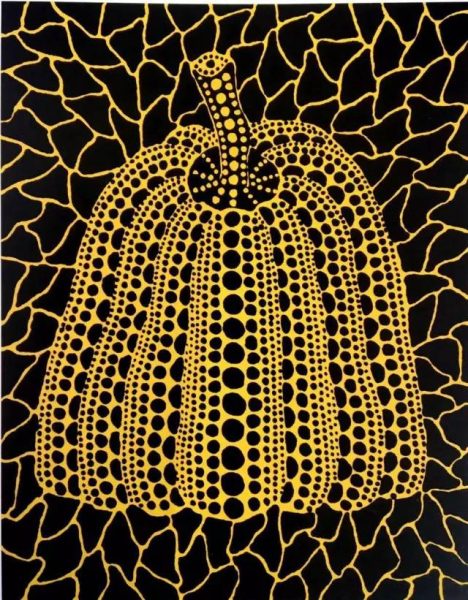

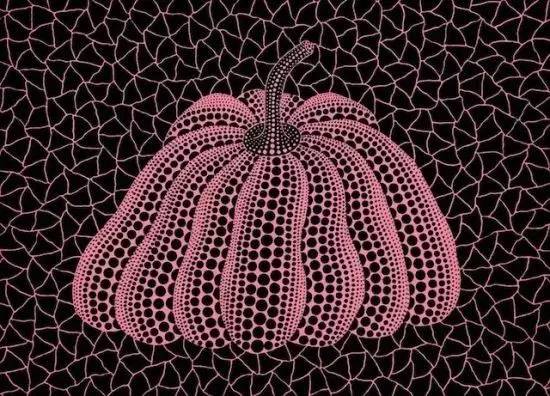

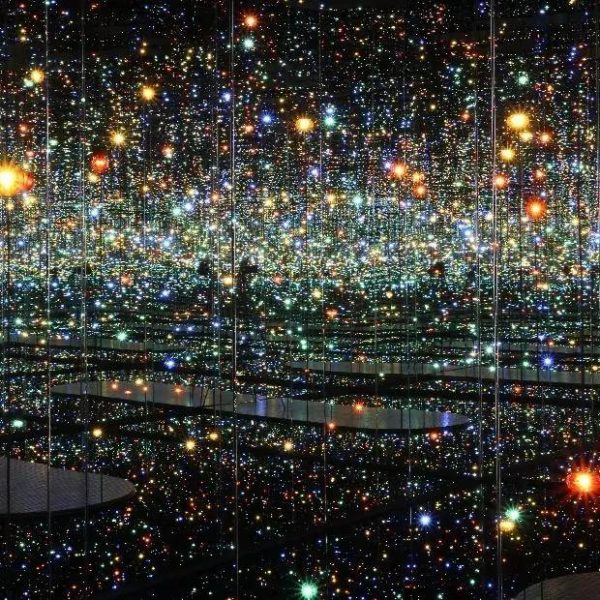

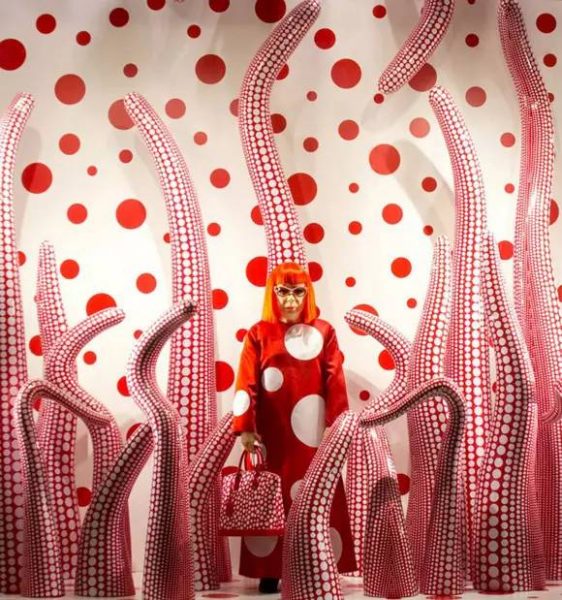

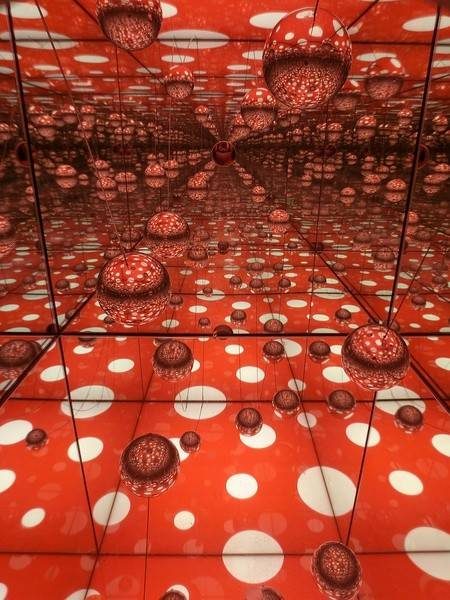

This major exhibition features new paintings – including her important, ongoing My Eternal Soul series and signature Infinity Nets – iconic pumpkin sculptures, and immersive mirror rooms, all conceived specially for this presentation. These new works reflect her lifelong preoccupation with the infinite and sublime, as well as the twin themes of cosmic infinity and personal obsession, as found in pattern and repetition.

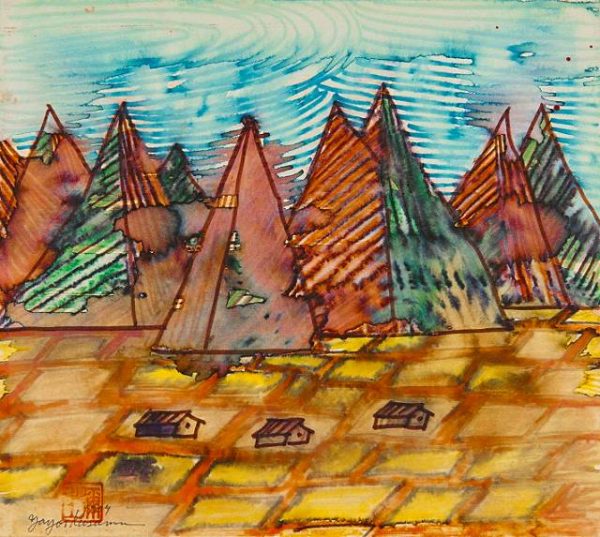

Yayoi Kusama was born in 1929, the youngest daughter of a well-to-do family in the mountainous region of Matsumoto in central Japan.

Her family made their living from the cultivation of plant seeds; there is still a plant nursery on the site of Kusama’s childhood home. Hers was a conventional upbringing, and when Kusama began to express enthusiasm in making art, her family were not wholly supportive of her interest. Her mother in particular discouraged her young daughter’s dreams of becoming a professional artist, trying to steer her instead towards a conventional path of traditional Japanese housewife. But Kusama’s persistence was strong. When her mother tore her drawings away from her, Kusama made more. When she could not afford to buy art supplies, she foraged in the house to find suitable materials with which to work. Some of the early paintings in the Tate Modern exhibition were made using jute sacking as a support.

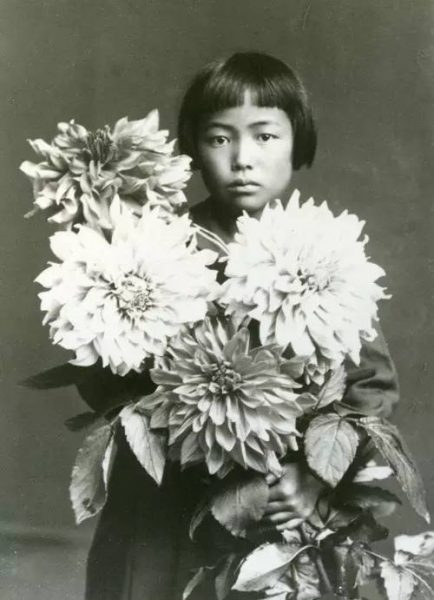

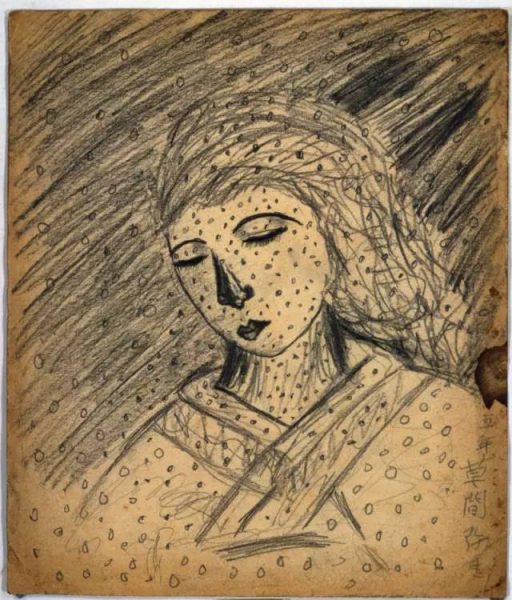

One early photo, taken at the age of about 10, shows a serious, rather beautiful girl with short hair, holding an enormous bunch of chrysanthemums. So upstanding was her mother’s family, that her father, a philanderer who spent much of his time in the company of geisha, adopted the Kusama name as his own. At around the time the photograph was taken, Kusama was already producing pencil sketches featuring dots and a net-like motif. Even a portrait of her mother, whom she hated for her strictness and prudish values, is covered in dots as though she were suffering from chicken pox. “My parents were a real pain,” she tells me. “I couldn’t stand it. They were very conservative. My family had been running the business for 100 years. My parents had old customs and morals.”

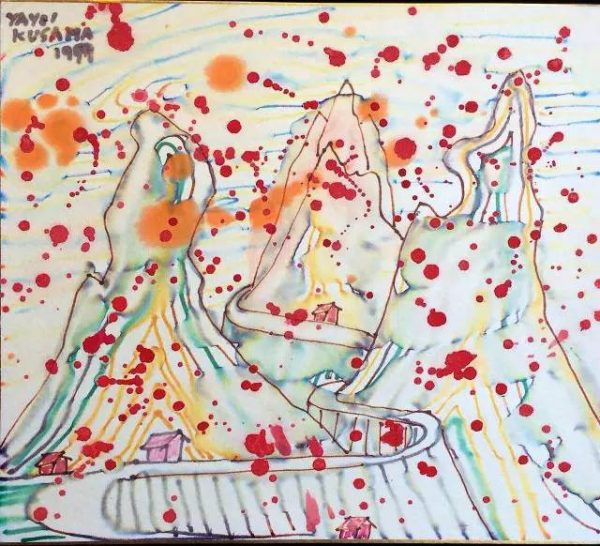

From early childhood Kusama experienced “visual and aural hallucinations”. In her autobiography, a document that, one suspects, is better treated as artistic statement than faithful record, she writes of her experience sat among a bed of violets. “One day, I suddenly looked up to find that each and every violet had its own individual, human-like facial expression, and to my astonishment they were all talking to me.” On other occasions, “suddenly things would be flashing and glittering all around me. So many different images leaped into my eyes that I was left dazzled and dumbfounded.” Whenever these hallucinations occurred, she would rush home and draw what she had seen.

Kusama’s early artistic ambitions were curtailed not only by her family. After the outbreak of the Pacific War, she, like other school-age children in her hometown, was called upon to work for up to twelve hours a day in a parachute factory. Despite this punishing work, she managed to find the time and the resources to continue drawing. An early notebook in the exhibition features page after page of beautifully detailed sketches of peonies made at this time.

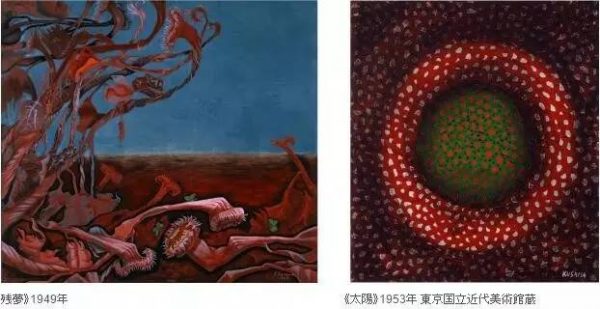

Kusama began publicly exhibiting her work in group exhibitions in her teens and in 1948, after the War’s end, Kusama convinced her parents to allow her to go to Kyoto to study painting in the Japanese modernist Nihonga style. She continued her studies in Kamakura City but soon grew tired of the conventional approaches of her teachers. Her great ambition and talent were recognised when she began staging solo exhibitions in her home town in the early 1950s.

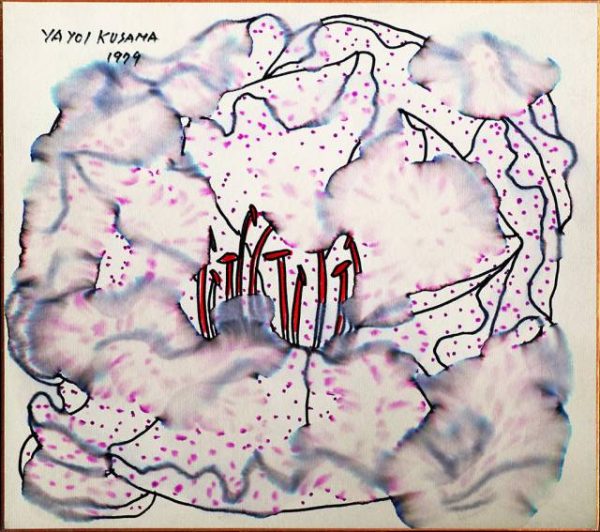

As a young woman, before she ever set foot outside of her native Japan, she was tackling formidable questions about life, existence and death, painting with odd combinations like oil and enamel on seed sack. Her first dots showed up in the beginning of the 1950s, though she experimented with them as early as 1939, in an untitled schoolgirl portrait of her mother. In “Heart,” a painting from 1954, you can feel her struggling to find a method and a voice as she creates diminutive gouaches in murky red and black tones. One of her works from 1950 carries the uber-heavy title “Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization,)” employing sodden black, brown and tan tones. You can also glean the modernist influences of Hans Arp, Lionel Fenninger, Wassily Kandisky and Jules Olitski at a time when few Japanese artists had accepted the covenants of Abstract Expressionism. One other artist was particularly influential as well — Georgia O’Keefe, with whom she began corresponding in 1955.

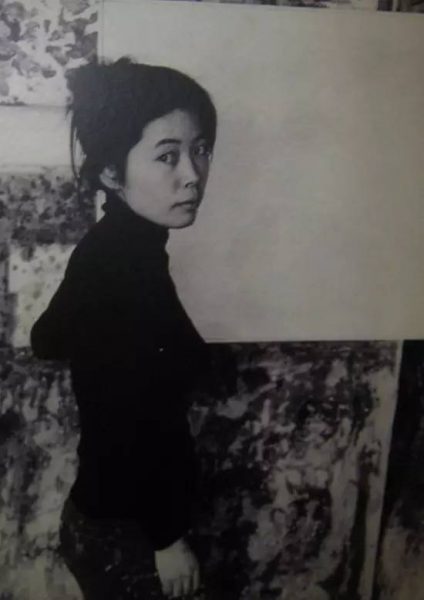

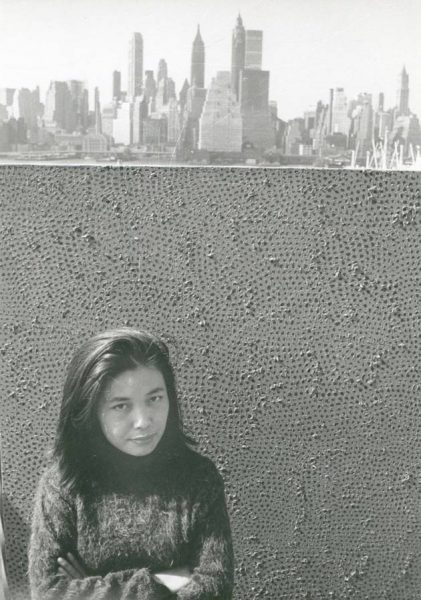

Kusama arrived in the United States from Japan in 1957, landing on the West Coast, in Seattle, and moving to New York in 1958. By 1961 she was included in the then Whitney Annual, jumping wholeheartedly into painting with thick whorls that must have used dozens of tubes of pure zinc white, as, for example, in the painting “Pacific Ocean.” She called these productions “nets,” examples of which fill one section of the museum. She also smacked right up against the 1960s, combining her obsessions about the nature of fear and the nature of the phallus with that decade’s hedonism, nudity, drugs and lack of boundaries. It made her trajectory so swift that in 1967 she directed a film about her own self-obliteration, which was shown in the New Filmmakers series at the Whitney.

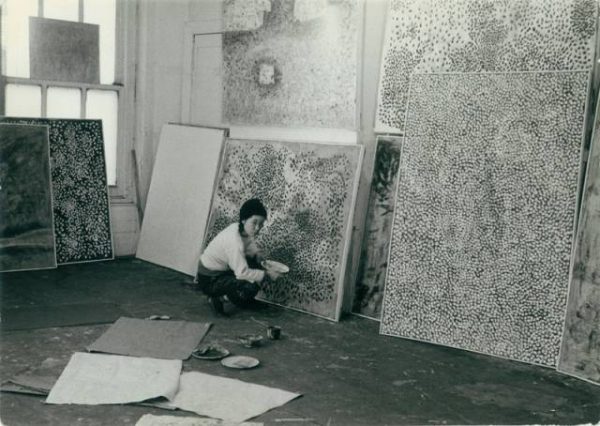

Her first years in New York, where she was to spend more than 15 years, were financially and psychologically traumatic. Winters in her unheated apartment were so cold she stayed up all night painting. She called it a “living hell”. But it did not lack for excitement. This was the era of Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Philip Guston and of pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Kusama, a frenetic experimenter, absorbed everything she could. Though she played on her exotic qualities as a Japanese women, often wearing a kimono, she became very much an American artist. “America is really the country that raised me, and I owe what I have become to her,” she wrote. Within a year she was ready to strike out on her own, telling a Japanese magazine, “I am planning to create a revolutionary work that will stun the New York art world.” The revolution came in the form of lace-like paintings that she called “infinity nets”.

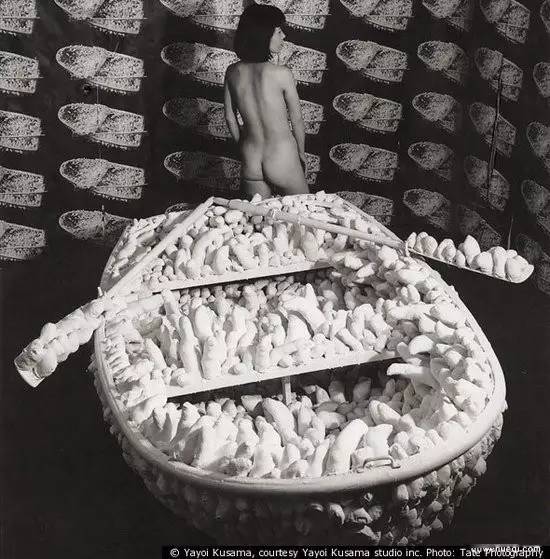

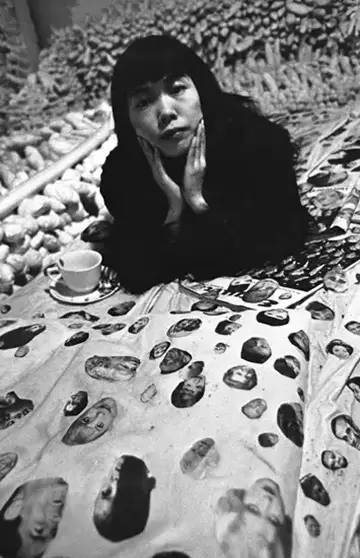

She filled huge canvases, sometimes more than 30ft-long, with endlessly repeated white loops of paint. Though it must not have looked that way at the time, the “infinity nets” were to become her defining creation. She sold some for as little as $200. Fifty years later, two months after Lehman Brothers went bust in 2008, one of her “infinity net” paintings, No. 2, was auctioned at Christie’s. It fetched $5.1m, a record sum for a living female artist. By the early 1960s, Kusama had moved on to so-called soft sculptures in which she covered everyday objects – sofas, ladders, shoes – in white sausage-shaped objects. The motivation was supposedly her distaste for the male organ, which she associated with her father’s extra-marital adventures. “I don’t like sex. I had an obsession with sex,” she tells me. “When I was a child, my father had lovers and I experienced seeing him. My mother sent me to spy on him. I didn’t want to have sex with anyone for years.” Much as with her dots, which she describes as helping to “obliterate” her anxieties through repetition, the rationale for sewing endless phalluses was to overwhelm her fears. “I make them and make them and then keep on making them, until I bury myself in the process. I call this process ‘obliteration’,” she says. She once told an interviewer, “I don’t want to cure my mental problems, rather I want to utilise them as a generating force for my art.”

In 1965 she produced “Infinity Mirror Room”, a precursor to her “Fireflies” installation currently at the Whitney.

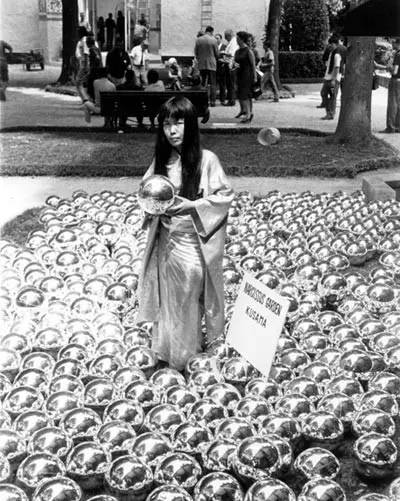

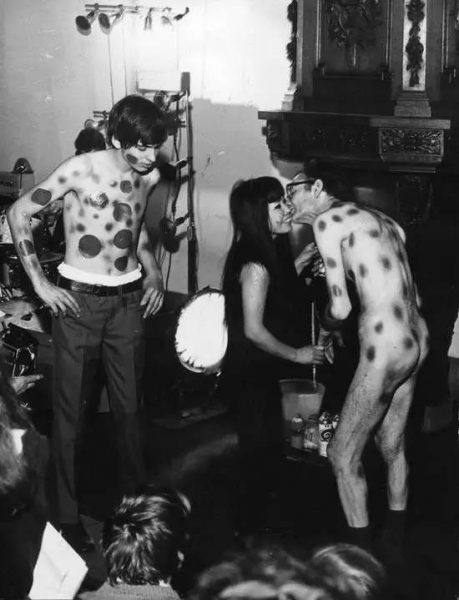

In 1966, heart problems now compounding her psychiatric afflictions, she went uninvited to the Venice Biennale. There, dressed in a golden kimono, she filled the lawn outside the Italian pavilion with 1,500 mirrored balls, which she offered for sale for 1,200 lire apiece. The authorities ordered her to stop, deeming it unacceptable to “sell art like hot dogs or ice cream cones”. Andrew Solomon, writing in Artforum many years later, said Kusama’s “lust for fame” had to be put into context. Comparing her to Andy Warhol – whom Kusama claimed had copied her – he wrote, “It should not be forgotten that she was less readily accepted since she was a woman; and battling for ground in a foreign tongue; and living in a society recovering from aggressive wartime prejudice against Japan.” Around this time, she began to stage “naked happenings”. It was perhaps the height of her fame, but a low point in her reputation.

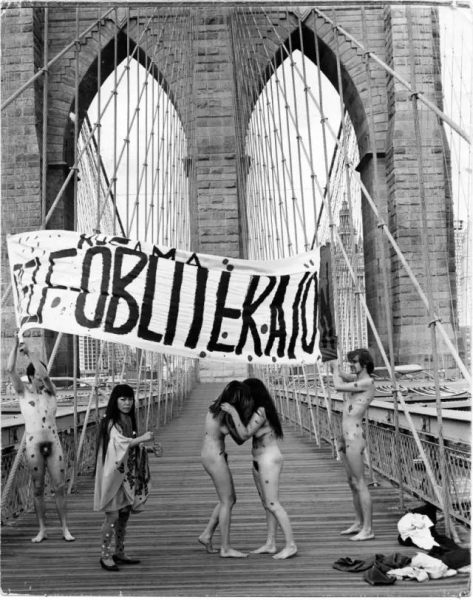

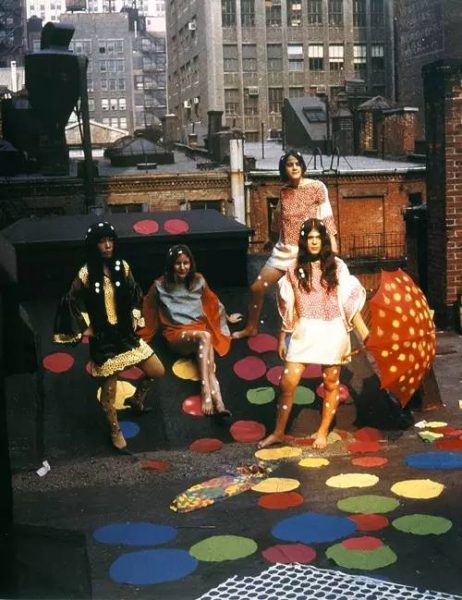

Bands of Kusama followers, whom she recruited through newspaper advertisements, would descend on a public place such as the New York Stock Exchange. There they would disrobe and cavort around to the sound of bongo drums, while Kusama, the Japanese sorceress, would daub polka dots on their naked bodies. They were called orgies, though the amount of actual sex that went on may have been minimal. Certainly, Kusama herself, still revolted by the male organ, never took part. Most of the happenings were, in any case, quickly curtailed by the police. One of the events – a sort of psychedelic pre-configuration of Occupy Wall Street – took place in the famous New York financial district. Kusama issued a press release in which she suggested, in capital letters naturally, that her aim was to “OBLITERATE WALL STREET MEN WITH POLKA DOTS.” In this, as in many things, she was ahead of her time.

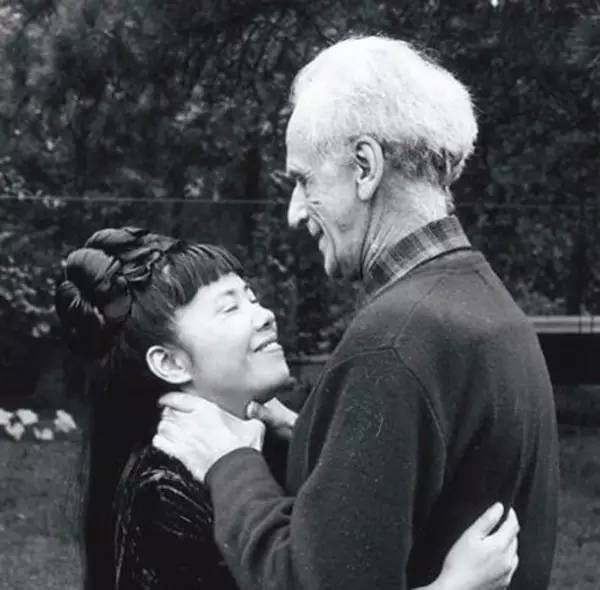

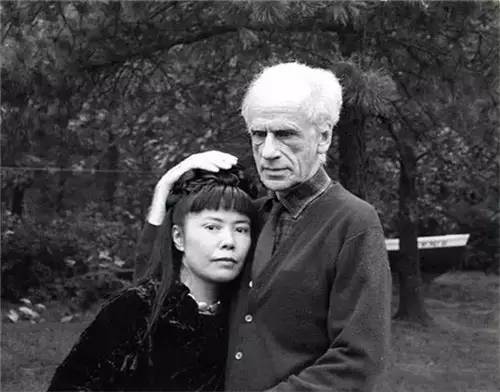

For an artist who advocated free love during her time as the high priestess of the hippies in late 1960s New York, Kusama is remarkably discreet about her own romantic connections.

She describes Donald Judd as an early boyfriend, but the artist with whom she forged arguably her closest relationship was Joseph Cornell. When they first met in the mid-1960s, Kusama was in her thirties; Cornell was twenty-six years her senior. Yet the two formed an unlikely bond that latest over many years. Kusama has described their relationship as passionate yet platonic. Cornell became infatuated with the younger artist, calling her several times a day and making and sending her charming collages with personal messages (‘Have some tea and think of me’; ‘Happy Easter to Yayoi’).

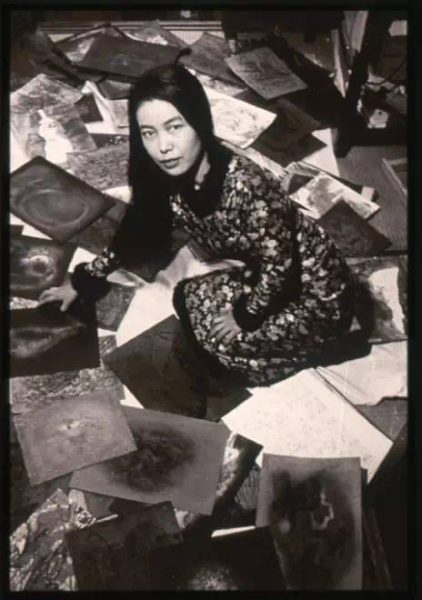

Kusama spent days at Cornell’s Queens home, where he lived with his mother. The two artists sketched each other; Kusama still owns a number of drawings Cornell made of her. At the time she was living hand to mouth, and Cornell, taking pity on her situation, gave her a number of his works to sell.

This early experience of art dealing was to lead Kusama to a temporary new profession on her return to Tokyo in the early 1970s, when for a time she acted as an art import agent, sourcing Western works to sell to Japanese clients. Her sales career was short-lived however, as the oil crisis and subsequent recession destroyed her market.

Cornell died in 1972, and Kusama felt this loss deeply. His legacy to her had not ended, however. When she returned to Japan she had brought with her boxes of magazine cuttings and other collage materials Cornell had given her. In the subsequent years, as Kusama began to build her artistic career again, she used these materials in a series of luminous collages. These works were to signal Kusama’s re-emergence to the Japanese art scene after her American sojourn. They also acted as a form of mourning for the American artist who had had such fondness and affection for her.

She loved no one else since.

In 1973 the party was over: money, already scarce, grew scarcer, and punk was redefining the aesthetic. Though her work was provocative and shocking, it didn’t pay the bills. She moved back to Japan and fulfilled the promise of her “self-obliteration” by promptly suffering a nervous breakdown. The reception was hostile. She knew no one and belonged to no Japanese art movement. “It must have been deeply humiliating for her to come back to Japan,” says Morris, the Tate curator. “She had a breakdown, she needed surgery, she had no money. It was burnout.”

Kusama checked herself into the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill and eventually took up permanent residence. She has lived there ever since. In the 1970s and 1980s she drifted into semi-obscurity, though she wrote poetry and fiction that won her a cult following in Japan. Only in 1989, when New York’s Center for International Contemporary Arts staged a retrospective and revived her art. She became more active again, mounting several one-woman shows in the US. In 1993, she went to the Venice Biennale, this time officially, where she produced a mirrored room filled with the pumpkin sculptures that are now central to her repertoire. Today, her silver pumpkins fetch around half a million dollars each. Kusama’s revival gained even greater force in 1998 with a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That was the same location where she had been stopped from staging an unauthorised protest 30 years before, “Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead at Moma.” Her career had come full circle, or to borrow the language of Kusama, it was repeating and obliterating itself.

She seems to have found her groove again by the 1990s, focusing more on pure design and color with large-scale paintings such as “Yellow Trees,” black-and-white dot paintings like “Revived Soul” and the green and black patterned “Weeds.” These works use repetitive patterns with a single color paired against black or white. The recreated “Fireflies” installation room at the Whitney offers a total, delightful immersive experience through the simple use of water, mirrors and hanging lights. Kusama’s paintings since 2009 have strayed into realms of pure pop design with a strong use of Matisse-like primary colors and cutout shapes, with mixed results.

Time and New York have become kind to her. She has triumphed where she was obliterated. She has been raised up where she had fallen. And that is the story of the long, strange art and life of Yayoi Kusama.