Kevin Macdonald’s 2016 documentary- produced by Wendi Deng- is a fascinating introduction to renowned Chinese contemporary artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s thrilling celestial artworks.

The Sky Ladder is a 1,650-foot ladder of fire climbing into the skies above artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s hometown. Creating ambitious signature pieces on the largest imaginable scales, Cai’s electrifying work often transcends physical permanence while burning its philosophies into the audience members’ minds. Told through the artist’s own words and those of family, friends and observers, this film tracks Cai’s meteoric rise and examines why he engineers artworks that loom as far as the eye can see.

Sky Ladder: The Art of Cai Guo-Qiang review – jaw-dropping pyrotechnics

Film review by Peter Bradshaw, extracted from THE GUARDIAN

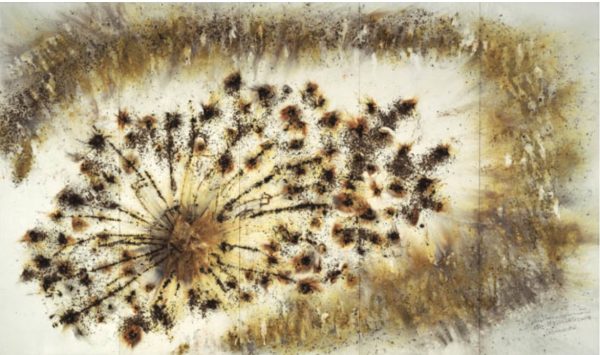

Nothing typifies the toweringly celestial ambition of the Chinese contemporary artist Cai Guo-Qiang than his “sky ladder”, a project over 20 years in the making. His jaw-dropping pyrotechnic concept involves a double-stranded firework connective wire suspended from a hot air balloon at night, with horizontal wires linking like rungs: when the blue touch paper is lit, a fiery spirit ladder appears to ascend infinitely into the darkness. It is transient and transcendental, like so many of Cai’s site-specific concepts, and like the Apollo spaceshots, many attempts were unsuccessful – including one in 1994 in Bath, of all places, which was cancelled due to rain. (Did anyone explain to the artist what the weather was like over here?)

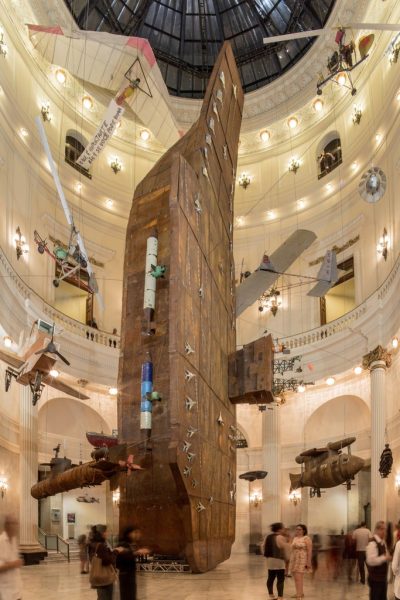

This documentary about his work – directed by Kevin Macdonald and produced by Wendi Murdoch – is fascinating. I actually found his other pyro happenings more interesting than the Sky Ladder, such as his daytime events, with bursts of multicoloured smoke instead of firebursts. His other creations, such as the airborne fighting dogs in Head On, are extraordinary.

Cai’s father was a gifted traditional painter and calligrapher who was oppressed during the cultural revolution, and Cai is clearly driven by some need to re-establish family honour, though he has a complex relationship with the Chinese state. He became a national megastar by devising the fireworks for the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony, but some thought he had sold out with a cheesier national event at the stadium: the 2014 Apec economic leaders’ forum. Even now, he has to take criticism from state sponsors, who say things like: “Mao taught us to be pragmatic and realistic.”

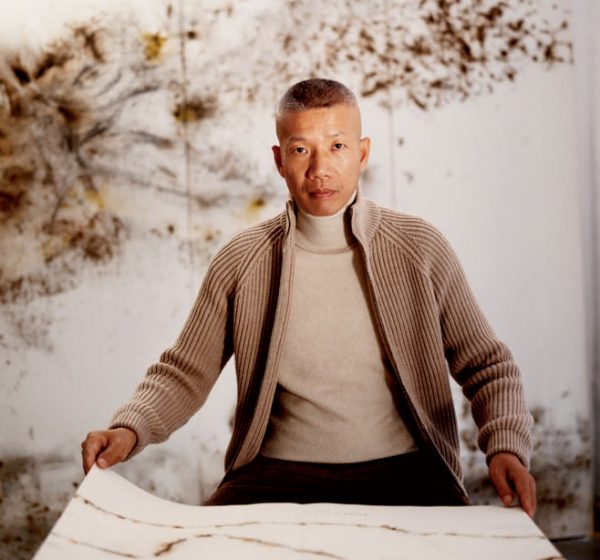

Cai Guo-Qiang was born in 1957 in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China. He was trained in stage design at the Shanghai Theater Academy, and his work has since crossed multiple mediums within art, including drawing, installation, video and performance art. While living in Japan from 1986 to 1995, he explored the properties of gunpowder in his drawings, an inquiry that eventually led to his experimentation with explosives on a massive scale and to the development of his signature explosion events. Drawing upon Eastern philosophy and contemporary social issues as a conceptual basis, these projects and events aim to establish an exchange between viewers and the larger universe around them, utilizing a site-specific approach to culture and history.

Cai was awarded the Japan Cultural Design Prize in 1995 and the Golden Lion at the 48th Venice Biennale in 1999. In the following years, he has received the 7th Hiroshima Art Prize (2007), the 20th Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize (2009), and AICA’s first place for Best Project in a Public Space for Cai Guo-Qiang: Fallen Blossoms (2010). He also held the distinguished position as Director of Visual and Special Effects for the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. In 2012, Cai was honored as one of five Laureates for the prestigious Praemium Imperiale, an award that recognizes lifetime achievement in the arts in categories not covered by the Nobel Prize. Additionally, he was also among the five artists who received the first U.S. Department of State – Medal of Arts award for his outstanding commitment to international cultural exchange. He has recently been awarded the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation Award in 2015, and the Bonnefanten Award for Contemporary Art (BACA) 2016.

Among his many solo exhibitions and projects include Cai Guo-Qiang on the Roof: Transparent Monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2006 and his retrospective I Want to Believe, which opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York in February 2008 before traveling to the National Art Museum of China in Beijing in August 2008 and then to the Guggenheim Bilbao in March 2009. In 2011, Cai appeared in the solo exhibition Saraab at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar, his first ever in a Middle Eastern country. In 2012, the artist appeared in three solo exhibitions: Sky Ladder (The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), Spring (Zhejiang Art Museum, Hangzhou, China), and A Clan of Boats (Faurschou Foundation, Copenhagen, Denmark).

His first-ever solo exhibition in Brazil, Cai Guo-Qiang: Da Vincis do Povo, went on a three-city tour around the country in 2013. Traveling from Brasilia to São Paulo before reaching its final destination in Rio de Janeiro, it was the most visited exhibition by a living artist worldwide that year with over one million visitors. In October 2013, Cai created One Night Stand (Aventure d’un Soir), an explosion event for Nuit Blanche, a citywide art and culture festival organized by the city of Paris. In November 2013, his solo exhibition Falling Back to Earth opened at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art in Australia. In 2014, he created solo exhibitions The Ninth Wave at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai and Impromptu at Fundación Proa, in Buenos Aires. On January 24, 2015, he realized Life is a Milonga: Tango Fireworks for Argentina in the neighborhood of La Boca.

His most recent solo exhibition There and Back Again opened on July 11, 2015 at the Yokohama Museum of Art in Japan. On June 15, 2015, Cai realized his most recent explosion event Sky Ladder off of Huiyu Island, Quanzhou, China.

Cai was the curator of the first China Pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005. Since 2000, he has also converted unexpected spaces into small-scale exhibition venues for rural communities and small towns in different parts of the world. This Everything is Museum series includes: DMoCA (Dragon Museum of Contemporary Art , 2000) in Tsunan Mountain Park, Niigata Prefecture, Japan; UMoCA (Under Museum of Contemporary Art, 2001) in Colle di Val d’Elsa, Tuscany, Italy; BMoCA (Bunker Museum of Contemporary Art, 2004) on Kinmen Island, Taiwan; and SMoCA (Snake Museum of Contemporary Art, 2013) in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan.