In Cai Zhisong’s most recent works, the Homeland series, how does the artist play with semantic tension? Compared with his previous series—Ode to Homeland, Rose, and Cloud—this new series is even more challenging in terms of how to create this tension. The subject matter of the Ode to Homeland series focuses on historical figures living in our imagination from the Book of Songs. Therefore, the realistic techniques are counterbalanced by historical imaginaries and fictions, and the result distinguishes itself from realism.

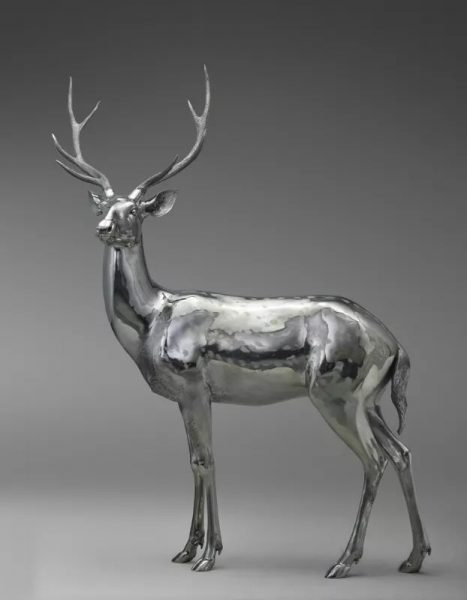

In Rose and Clouds, to achieve semantic tension is relatively easy. Roses and clouds, due to their fragile and elusive natures, are not considered a conventional subject matter for sculpture. Thus when Cai Zhisong approaches roses and clouds in a realistic fashion through the language of sculpture, surprise is already present, as do many difficulties with plastic design and realization. But it is another story with the crane and deer: they are real animals that are not particularly hard to find in real life, and they have been favorably portrayed throughout history by generations of sculptors. Or, in other words, there have long existed certain stereotypes of these two animals, particularly schematized in the fields of craft and the fine arts. In the case of crane and deer, therefore, it is not an easy task to create semantic tension through realistic language. However, Cai Zhisong is wholeheartedly ready for the challenge. Out of a kind of religious piety, together with his excellent skills, he hopes that these crane and deer sculptures could ultimately transcend the average artifacts produced by mediocre craftsmanship. He embraces the technique of realism, craft, and fine art—and beauty as well—pushing them to even higher levels; he has successfully transformed the ordinary crane and deer sculptures into extraordinary artworks.

When the utmost fineness and beauty is achieved, these animals become immortalized as works of art, and the man-made artifact unites with a transcendental spirit. When the two spirits in two different forms—sculpture and animal—converge into one, so too do the artistic and transcendental ideals. The animistic features in the crane and the deer render a layer of mystery onto Cai Zhisong’s sculptures, whereas Cai’s sculptures elevate the animals to the spiritual world – a heavenly existence indeed. In Cai Zhisong’s Homeland series, the semantic tension comes not from a conflict between the normal and the eccentric, but the distance between the worldly and the transcendental. In Cai’s works, the semantic tension lies in his attempt to convey the transcendental and spiritual—things that are beyond human language—while resorting to tangible and conceivable figures, such as these worldly, ordinary animals.

Specifically for his solo exhibition at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum in December 2017 last year, Cai Zhisong has been developing this project for quite a long time. In search of materials for the work, he travelled as far as the Zha Long Natural Reserves to study the red-crowned crane, and he even bought a pair of sika deer from a farm. The choice of subject matter this time, i.e. the crane and the deer, is motivated by the spirituality and the good fortune and peace that these two animals signify in traditional Chinese culture. Crane and deer are frequently depicted as joyous subject matter in traditional painting and sculpture. In the contemporary art world dominated by the critical spirit, however, it has become rather rare for animals to appear with a positive energy. That said, to depict animals in a negative way in fact runs a greater risk.