‘Nothing can touch me now- I am Jeff Koons and my art can defend me!’

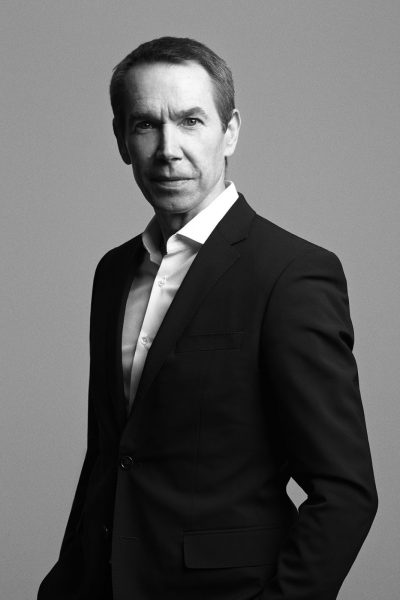

He is one of today’s most acclaimed contemporary artists, whose monumental pieces are exhibited in museums around the world, and whose interests extend to blow-up toys, household appliances, kitsch and luxury fashion accessories.

American contemporary artist Jeff Koons has produced a parade of eye-popping works that include Balloon Dog, an outsized steel sculpture that looks as if it was made from twisted-together party balloons, Rabbit, a stainless-steel cast of an inflatable bunny; Puppy, a 43ft-high West Highland terrier embedded with living flowers; and Play-Doh, a copy of a multicoloured lump that one of his sons made as a toddler – only this took 20 years to complete and is almost twice the height of the average person.

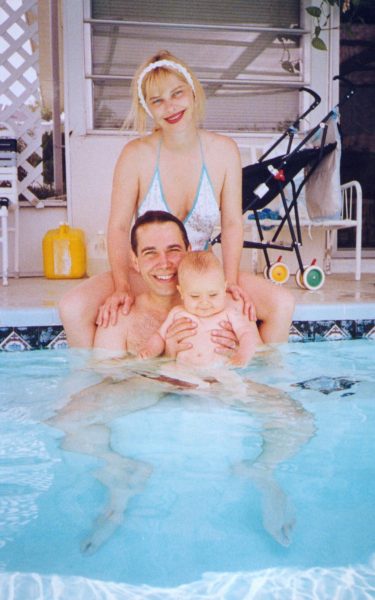

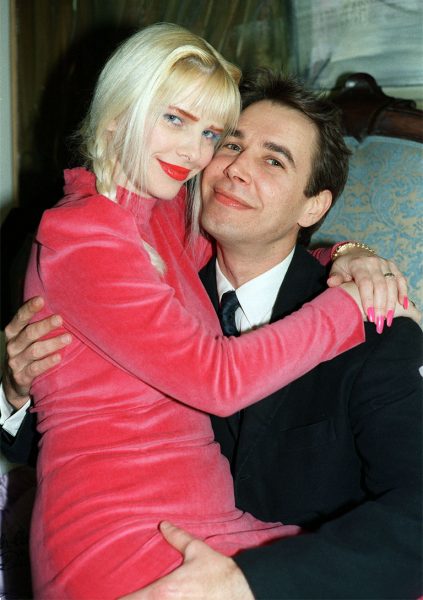

He has also turned his most intimate moments into art, appearing in flagrante with his first wife, the porn star and politician Ilona Staller (known as La Cicciolina) in a series of controversial photographs and sculptures.

Everyone agrees that he is the world’s most expensive living artist. In 2013, Balloon Dog (Orange), sold for $58.4 million.

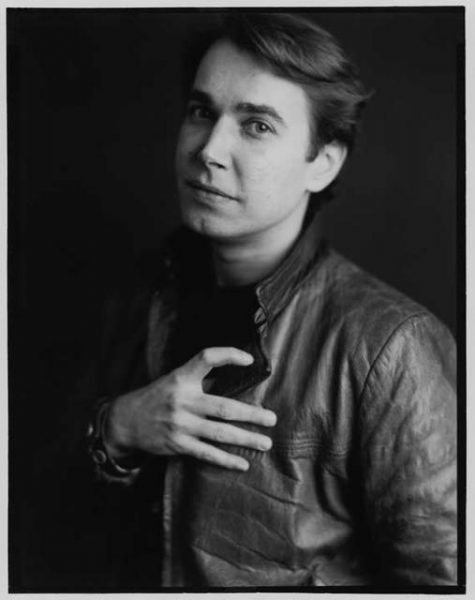

Opinions on his art differ. Robert Hughes, the late art critic, thought him a ‘starry-eyed opportunist’, whose success was down to aggressive self-marketing. Others are in awe, seeing him as one of the most original and sensational artists of the 21st century. At 62 Koons looks much like he did at 32: handsome in an American way – clean, neat hair, perfect teeth. He is dressed in a navy-blue shirt and spotless dark jeans.

He may produce art with a playful edge, but in person he is soft-spoken with a strange earnestness. His art goal, he said, was ‘transcendence – to help people find something of greater interest than self’.

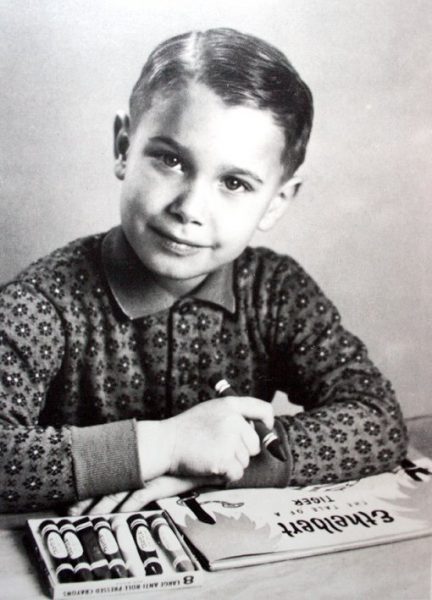

Jeff Koons spent his early years in York, an old industrial city in Pennsylvania. His father, an interior decorator, owned a furniture store and his mother was a housewife and seamstress who made wedding dresses. ‘When my father designed an interior, he would sit down and sketch everything out on graph paper.

‘If you ordered a sofa from my father, and a love seat, and a lamp and a mirror, you knew exactly what you were getting because he would create a drawing that would be very, very precise.

‘You wouldn’t envision a lamp of 4ft tall and receive a 12in one,’ he says. ‘He taught me vision and that sense of caring.’

He started taking art lessons at the age of seven. By nine he was painting copies of old masters, which his father sold in his showroom for up to $700. He spent some of the money on electric road-racer sets – a popular toy in the 1960s.

His early teenage years were more rebellious. ‘I think I was bored,’ he says. ‘I didn’t have a lot of outside stimulation so I was probably a little wild – just mischievous; probably drank a lot of beer.

‘But eventually, around 15, I decided I really wanted more and I kind of pulled away from some of the friends I’d been hanging out with. I had a girlfriend who was much more serious about her studying and school, and I started to really think about creating my own future.’

He studied art in Baltimore, transferring for an influential final year to the Art Institute of Chicago, where he was taught by Ed Paschke, one of the ‘Chicago Imagists’, a group marked by irreverence and attention-grabbing populism. Koons got pushed into avant-garde circles.

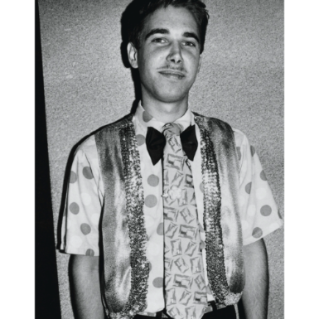

He settled in New York in 1977 and got a job selling memberships at Museum of Modern Art, where he was noted for his outfits – polka-dot shirts, floral vests, big bow ties, and an occasional inflatable plastic flower – and for doubling the membership roll (he is adept at selling and supported himself for five years as a highly successful commodities broker).

By now he was producing his own work: inflatable plastic toys placed on shop-bought mirrors. He progressed to small kitchen appliances, as well as vacuum cleaners and carpet shampooers encased in brightly lit glass display cases.

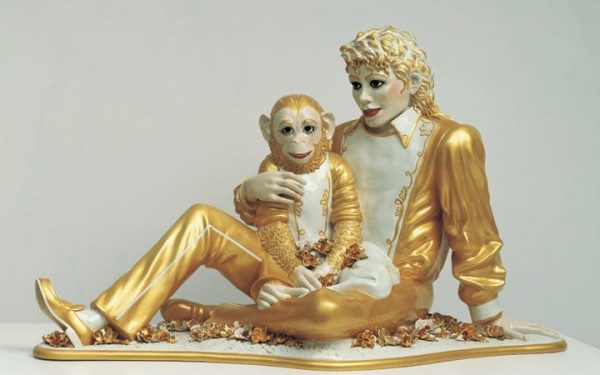

A turning point came in the mid-1980s when Charles Saatchi, the advertising and public relations executive, then one of the world’s most active buyers of contemporary art, started acquiring works by Koons. But it was Banality, an exhibition held simultaneously in New York, Chicago and Cologne in 1988, that made him an art star.

Each of the works – including the Michael Jackson & Bubbles figure– was made in triplicate, and the show earned Koons a lot of money. And yet the rise hasn’t been smooth.

In the ’90s he nearly lost everything. By 1993 his private life was cracking up, with the divorce from Staller and a custody battle over their son, Ludwig. Although the US courts had awarded custody to Koons, Staller fled to Rome with baby Ludwig, and the Italian courts awarded her custody of their child.

Koons spent millions of dollars in legal battles over the next decade but without success. ‘I ended up selling everything,’ he says – proofs (or ‘artist’s copies’) of his earlier sculptures; prized works by Roy Lichtenstein. ‘I ended up not having any money.’

At the same time, he was struggling to complete a series of works called Celebration, which focused on the things children love: party hats, birthday cake, Play-Doh, a dog made from party balloons. ‘Celebration was a way for me to connect to a larger audience but at the same time it was so my son could understand that I was thinking about him,’ he explains.

But escalating fabrication costs and technical problems – nobody had tried to make stainless-steel sculptures this complicated – meant the money ran out (the project was revived in the late ’90s). Staff were laid off, leaving a team of two: Koons’s studio manager, and Justine Wheeler, an artist from South Africa who had arrived in 1995.

Koons credits his comeback to ‘art’ and to Wheeler. They married in 2002 and went on to have six children: Sean, 15, Kurt, 13, Blake, 11, Eric, 10, Scarlet, six, and Mick, four.

Koons uses industrial processes in his works: he gets an idea, and a team of assistants, specialists and fabricators make it, with Koons controlling every step along the way.

He currently employs 148 people at his studio, and several are working at large-screen computers in the outer offices – large, white, windowless rooms with grey concrete floors.

Koons sits, in solitary splendour, at a white table in the centre. He likes things ‘simple’, he says. And on his desk is a neat pile of books, a laptop and a plastic sandwich bag filled with Cheerios. At first I took the breakfast cereal to be the prototype for a new art piece, but it turns out that Koons likes to snack on them throughout the day. ‘I love Cheerios!’ he says, cheerily.

Koons is focused on pushing materials to their limits and demands flawless execution. To achieve the reflective brilliance of the stainless steel he used for Balloon Dog, for example, took months of polishing and many remakes. He wanted every fold and crease to look balloon-like.

In early 2015, Jeff Koons took a call from Delphine Arnault, the executive vice president of Louis Vuitton, who asked if he’d like to collaborate on a collection of handbags. This is not the kind of creating Koons normally does.

‘I knew it would be a really large commitment, because if I make something, I really want to make something that’s worthy of spending that energy and time, and hopefully create something that has a profoundness about it, and a reason for being.’

Bernard Arnault, Delphine’s father, and the chairman and chief executive officer of the LVMH group (which owns Louis Vuitton) is a collector of Koons’s work.

He first collaborated with the group about six years ago when he produced a limited- edition champagne- bottle holder (and bottle and case gift sets) for Dom Pérignon (also owned by LVMH).

Based on his sculpture Balloon Venus, the 2ft-tall, fuchsia figure cost $20,000 (not including the bottle of champagne). What Koons liked was the group’s access to top-quality technical know-how. ‘They work with companies involved in moulding, production, colouring, and have everything at such a high standard,’ he explains.

Koons divides his time between his house, a mega-mansion on the Upper East Side, and a 170-acre farm in Pennsylvania that once belonged to his maternal grandparents.

The American artist doesn’t want space trouble even in his private life, and for a big family like his one – a wife and five children – he needed an appropriate home. As it was impossible to find in Manhattan house of the right dimensions, Koons has soon decided to buy two, nearby, and unite them. As result, the 21,000 square feet space in the Upper East Side, makes of the Koons’ mansion one of the biggest single-family house in the rich New York neighbourhood.

The addresses are 11 and 13 East 67th Street: the two buildings cost to the artist approximately $ 22 million, to which adding $5 million of planned as renovation costs.

He likes routine, working Monday to Friday, from 9am to 5 or 6pm. He is reluctant to discuss money.

‘The real value of art isn’t in the monetary part,’ he says. Koons likes to see himself as a person who opens up art. ‘My work is always trying to break down the hierarchy or the disempowerment that art can make people feel,’ he explains.

‘It’s a symbol of store value but that is not its real value. Its real value is that hopefully people will embrace the world around them more.’ But then, reviewing his output and his success, he says, ‘I must admit I have to pinch myself sometimes.’

*extracted from the Telegraph